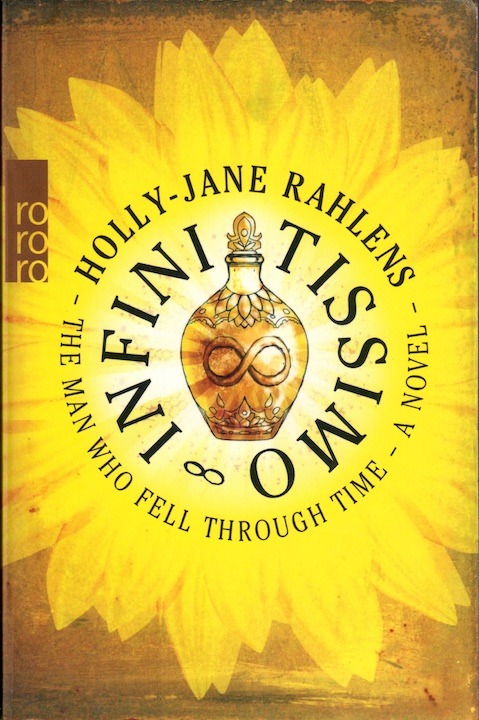

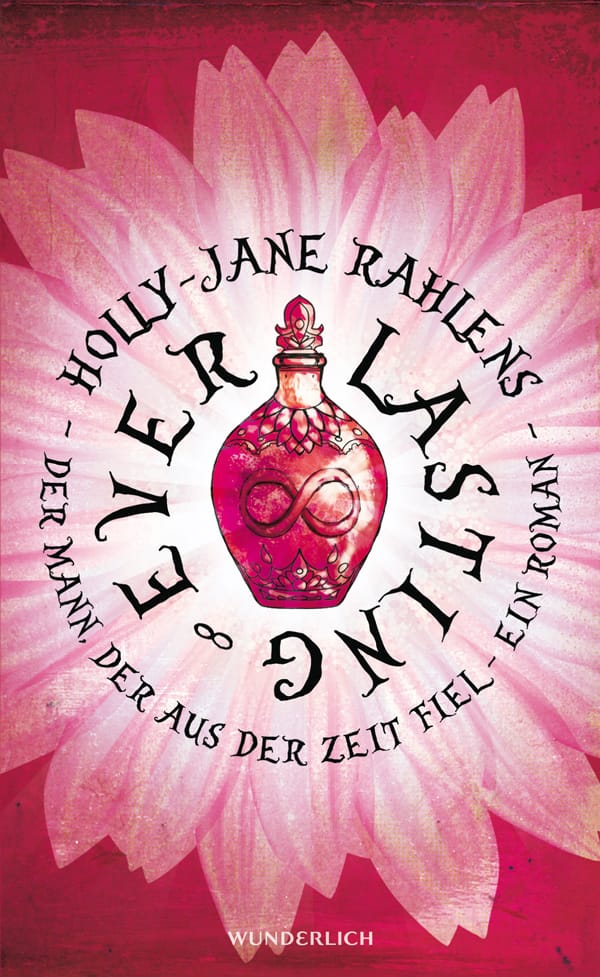

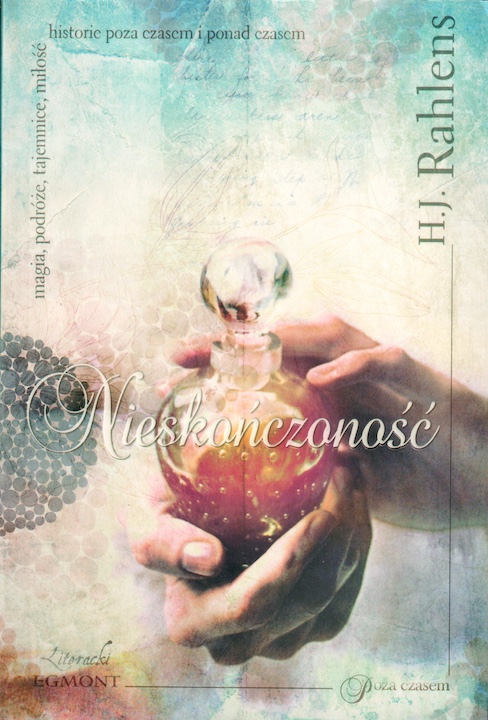

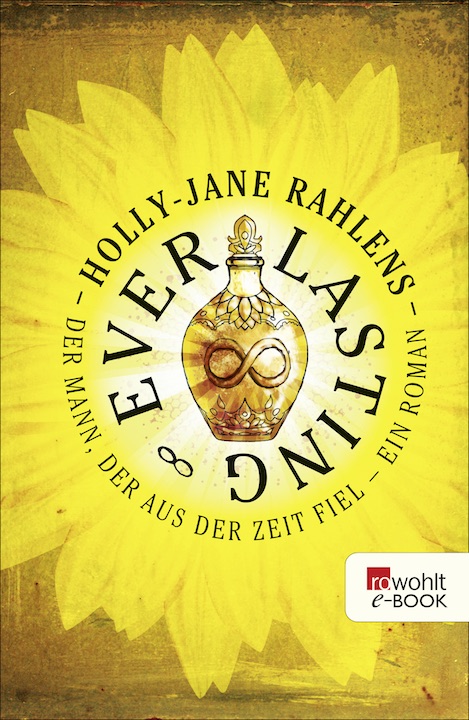

Infinitissimo

The Man Who Fell through Time

Infinitissimo is the tale of a quest through time and space to rescue a lost emotion — love.

![]()

![]()

![]()

It’s the year 2264. Despite incredible technical advances, scientists of the 23rd century are at a loss to solve the problem of a decimated human population. The young historian Finn Nordstrom, a specialist for turn-of-the-millennium popular culture, is asked to translate newly-discovered diaries written by a young girl in extinct German. Do these early 21st century vintage diaries hold a secret that can revitalize humankind?

Finn Nordstrom lives in a passionless but otherwise worry-free and peaceful world shaped by community spirit, leaps in science, and the promise of immortality. All is well until he begins decoding Eliana’s diaries. Following the progression of her life from page to page, he becomes fascinated by the young girl blooming into womanhood before his eyes. Asked to test the authenticity of a virtual-reality game set in the twenty-first century, Finn is stunned to find himself face-to-face with the girl. Caught up in a whirlwind of intrigue orchestrated by powerful physicists, Finn is sent unwittingly on a dangerous mission through time.

Radio Interview in English

The Story Behind the Story

Three years ago I was asked in an interview for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung’s young people’s page if I had any tips for young future writers. I suggested saving one’s school essays and putting them neatly in a safe place. Stories we write when we’re children can often be quite embarrassing a few years later. But that’s perfectly fine, for it allows us to see how we’ve changed, how far we’ve come aesthetically, and that helps strengthen our commitment as writers.

An old piece of writing can even inspire a new story. When I was in the fifth grade, for example, one of our assignments was to write a fiction piece about the future. I remember really enjoying this assignment. Proud of my “A,” I saved the composition and “put it neatly in a safe place.” Seven years later, when I was a senior in high school and we were writing about utopias, I took another look at the composition — and was shocked. How naive I had been as a child! How superficial. And silly. Why the composition didn’t land in the garbage, I’ll never know. But I’m certainly happy today that it didn’t!

The composition is dated January 31, 1961 — just ten days after John F. Kennedy’s inauguration, for many Americans an extremely optimistic, forward-looking time. At ten, though, I was interested neither in politics nor in the near future. My story was called “A Letter Through the Time Barrier.” It was addressed to a girlfriend in the 20th century from a fictive “Holly” who resided in the future, in the year 9000. I wrote to Charlotte telling her about our wonderful world where neither war nor crime was known, where humankind lived honestly and where every grade school had a swimming pool in the schoolyard. We future beings were clearly happily in contact with the past. Our scientists had figured out how to communicate with people who lived some seven thousand years before. It was easy: we simply sent letters per Airmail with the United States Post Office. They were there the very next day.

I’m thrilled that I still have this composition. When I read it now, I’m touched by my innocence, my naiveté. My earnestness. “A Letter Through the Time Barrier” says a lot about the dreams, the hopes and the child-like imagination of the ten-year-old Brooklyn girl that I once was, but also — and this is more important — about the child that still lives within me.

When I dug out this composition for the interview after so many years and read through it, I literally felt my heart beat faster. I knew at once that I would write a book that took place in the future. And similar to “A Letter Through the Time Barrier” it would break through the confines of time and space. I longed for the richly imagined worlds that had seduced me as a child.

After writing four (relatively realistic) young adult and all-age novels, I was keen on writing again for an adult audience. But the Fantastic, Science Fiction and the workings of imaginary worlds have more or less been banned from serious contemporary fiction. Can we really write such a book? My ten-year-old self, a child of her times, says, “Why not? In every reader lives the need for the fantastic.”

The questions I posed for the book have a lot to do with me today as a daughter, mother, wife, girlfriend and writer. I thought a lot about them (and researched them and discussed them with experts): What will life be like for humankind in 250 years? Will we be living in nuclear families or in extended families? In communes perhaps? Or maybe the family as we know it today no longer exists. Who will look after the children? Will there still be schools? Universities? How will our children be educated? Will books still exist in two centuries? Will people even be reading? Will they write? If so, how? With pens and pencils? Or just digitally? How is information received and transmitted? Does the internet still exist? Will computers still be in use? How will our language have changed? What do we do for entertainment? What foods do we eat? What do we drink? And our cities — what do they look like? Specifically: how has Berlin, one of the book’s main locales, changed over the past 250 years? Why did things turn out the way I’ve made them turn out? And very important: how about love? And sex? And how do I wrap that all up into a story that’s entertaining, makes us think, touches us, and tells a story that reflects our times in a believable way, as well as an imagined future time?

The world I created is — save for my rather daring but always exhilarating flirt with time travel — fairly realistic. My characters don’t live in a dark and bleak totalitarian society. In 2264 humankind has recovered from a long stretch of hard times that now lie almost two hundred years in the past. Humankind has learned to embrace community spirit and take responsibility for their society and their environment. The world is a comparatively peaceful place, but … . Yes, there’s a “but.” Without a “but” we don’t have a story, do we? Finn Nordstrom, a young and sensitive historian from New York, a specialist for the extinct language German, says “but” and … falls out of time.

My ten-year-old self would have been too young to read and understand this book, but she played a role in its making. Without her, her child-like imagination and her composition “A Letter Through the Time Barrier” I would likely never have written “Infinitissimo.” Enjoy!